I was at the coffee shop when my son called with suicide on his mind. He was deep in a hole of addiction, self-loathing, anger, and resentment.

He was scared. “Can you come?” he asked.

Two hours later I was on a plane to Seattle, and by evening I was by his side, trying to talk him down. But he was in a bad way, and he had been in a bad way for a long time, and nothing I could say would snap him out of it and make everything better.

A few nights after my arrival, he overdosed on fentanyl and booze. The 911 dispatcher led me through what to do until the ambulance arrived, and half-an-hour later, he was safe in the hospital.

He needed rehab and professional help.

The first thing I had to do was help him pack up his stuff, clean his apartment, and get him out of Seattle.

How I grew to hate the filthy streets of that city, the homeless tents crowding the sidewalks, the addicts shooting up on 3rd, the madmen screaming nightmares in the streets.

One morning I saw a young professional woman chattering into a cellphone in her left hand while in her right, her poodle pissed on a homeless man’s tent—a perfect image of clueless luxury meeting abject misery.

Plucking my son from Seattle’s machinery of hell was a real trial of soul. I braced myself and began doing what had to be done, but I was a mess.

I was embarrassed and full of shame. “If my son was in such a fix,” I thought, “I must be a shitty father,” then recoiled in angry self-defense. “It’s not my fault!”

Most of all I was worried to death about Zak and pissed at him for worrying me to death.

In this wonky mix of fear and anger, gritting my teeth for the work ahead, I went out one morning to the Bartell Drugs store to buy some packing tape.

At the entrance a homeless man was sitting on the filthy concrete. “Yet another soul lost in this urban wasteland,” I thought.

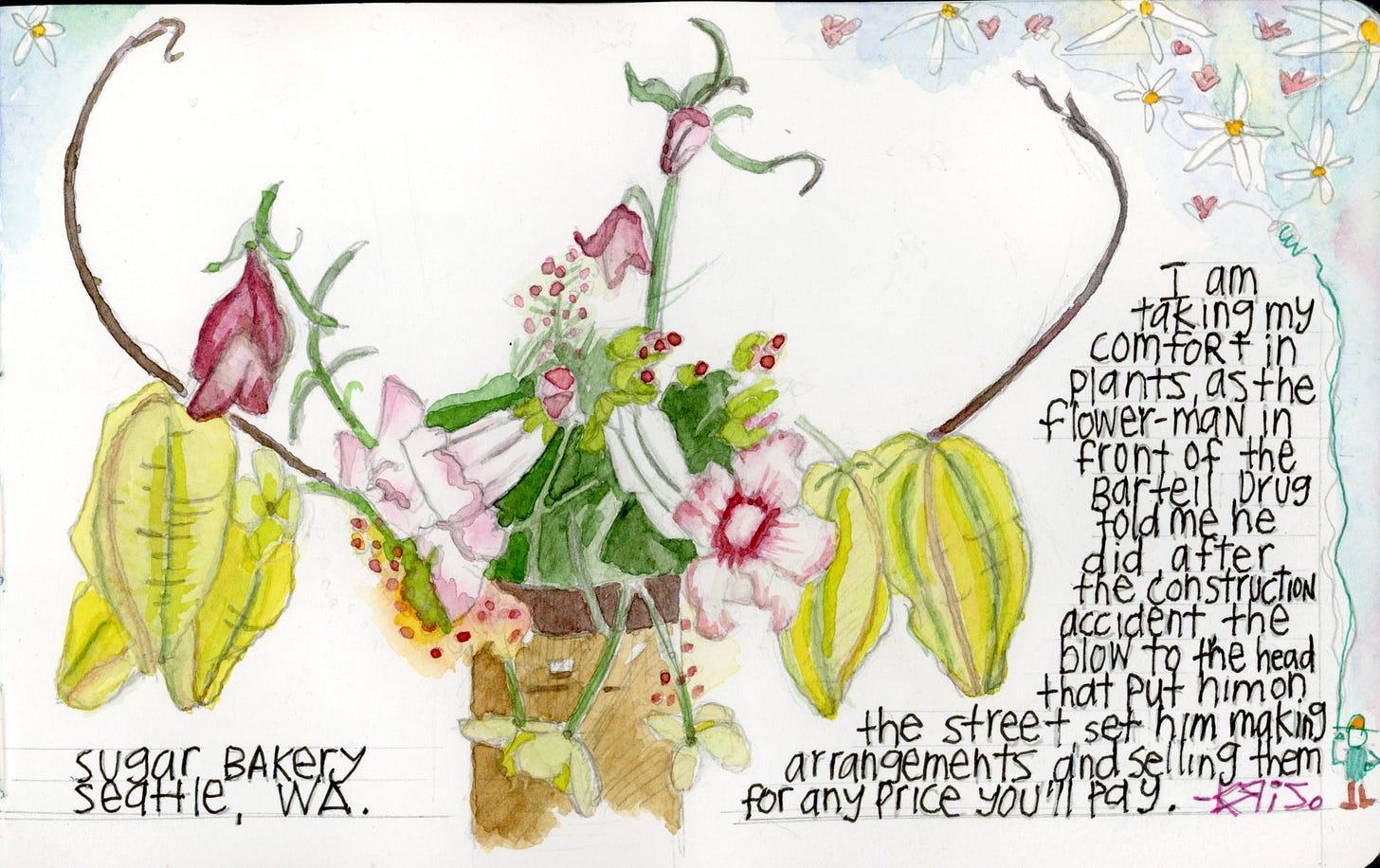

But as I drew closer, I saw he was surrounded by flowers. Wildflowers. Violet Asters, chocolate lilies, bleeding hearts gathered into little bouquets in glass jars and rusty soup cans.

I stooped down to look closer. Each vase of flowers was unexpectedly beautiful, constructed with artful spontaneity. The man had a feel for flowers.

“How much?” I asked.

“Whatever you’ll pay,” he replied.

His name was Kenneth. He had been a construction worker, he told me. A blow to the head on a job site had done permanent damage and had put him on the street. Only flowers, he told me, brought him any comfort, so he decided to turn the comfort into cash for food and in this way to keep on keeping on.

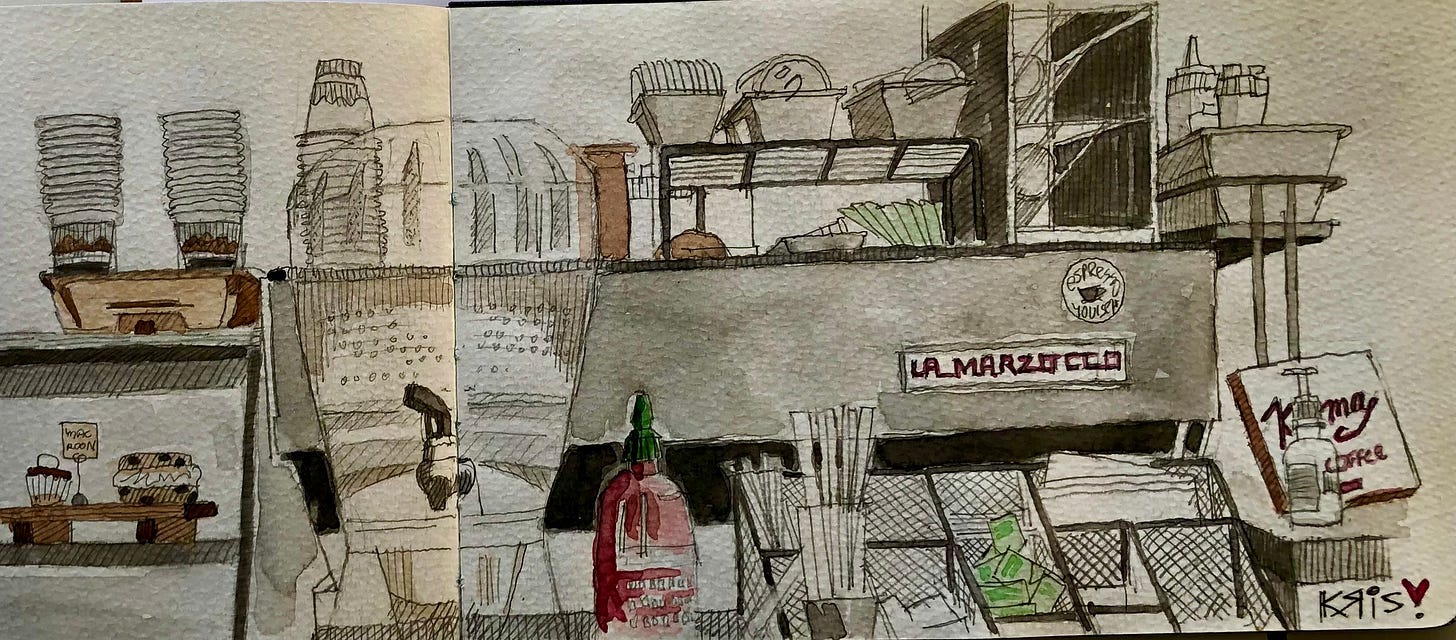

I gave him a 10, brought the arrangement back to my son’s apartment, and set it on the kitchen table. Before another day of packing and cleaning, while having my coffee, I sketched Ken’s flower arrangement.

Sometimes the only thing one can do in the confusion, fear, and sadness of life is to stare. Overwhelmed by fear and grief, the mind goes catatonic, incapable of reflecting in any serious way.

It is not a bad state of mind in which to draw; there is a kind of openness in it.

When my eye looked out, blank and disconnected, and I saw these wildflowers, something of the green and growing world, its peace and grace, trickled into my soul.

As I drew, something more came into me as well.

Ken’s flowers were such wild, gentle things, the tendrils turning such soft curls and the flowers hanging in such beautiful surrender, that they filled me—strange as it may sound—with courage.

Their delicate beauty, blooming in such a concrete-and-asphalt world, gave me something of the hope I was going to need to face this family crisis and to bear the awful vulnerability of loving my son.

That horrible week in Seattle was the beginning of a long road of rehab and recovery. Slowly and with great difficulty, my son rebuilt his life.

His willingness to cry out for help and to face his own demons transformed our family. It opened up a larger understanding of ourselves and a deeper love for one another.

But that redemption was still two years away.

My son turned in the keys to his apartment, and I threw away Ken’s flower arrangement. It had withered and dried up in its rusty can, but it had done its work.

If you like the art, click the heart! It increases my visibility on the Substack platform! And please share Tulipwood with your friends and family. Thanks!

Beautiful…

That must have been very difficult to write about and remember...all beautifully said but such an anxious story. Glad Zak is in a better place for sure and thank goodness for Ken's flowers.