It was 1927.

Charles Lindbergh was crossing the Atlantic in The Spirit of St. Louis. Philo T. Farnsworth was transmitting the first electronic TV image. The Great Mississippi Flood was inundating 16 million acres of land, and Clara Bow was the “It” Girl.

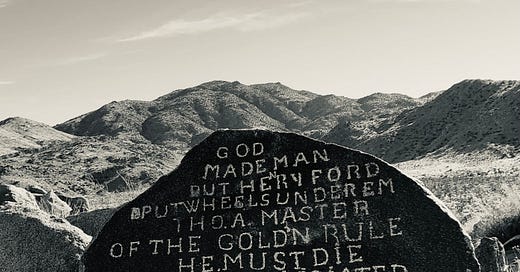

Meanwhile, a crazy Swede was homesteading in the Lost Horse Valley of the Mohave Desert and chiseling his thoughts into the biggest, flattest volcanic boulders he could find.

Talk about writing into the void.

His name was John Samuelson, but he was a nobody. It’s not easy to write when you’re a nobody, living in the middle of nowhere, with no one within 100 miles to read your stuff. (Sound familiar, anyone?)

Even a nobody needs a sympathetic ear, and sometimes it doesn’t matter to whom the ear belongs.

When Chuck Noland, the Fed Ex employee played by Tom Hanks in Cast Away, is abandoned on a Pacific island, the only way to keep himself from going crazy with loneliness is to talk to Wilson, his volleyball.

A lonely creature will make a friend even of a rock.

Samuelson certainly did. He poured out his heart to the boulders behind his homestead as if they were regulars at his local bar. Just like one of the boozers, he sometimes grew philosophical.

On one rock Samuelson chiseled his philosophy of life down to three simple points.

Nature is God.

Evolution is the Mother and Father of Mankind.

The Key to Life is Contact.

It’s the philosophy of a desert homesteader, as simple and clean as the desert itself, and though it was picked out with a hammer and chisel, it’s surprisingly modern.

Samuelson was right: “The key to life is contact.”

But clearly contact with Nature was not enough for him. His stony posts prove it. In all his chiseling, Samuelson was looking to make contact not with rock but with his fellow man.

We can cry out into the starry night, hoping to make contact with the Big Something that we all like to squeeze into a Little Word—Nature, Yahweh, Brahman, Tao, Allah, God—but in the end we need a hand to hold.

Man is a lonely animal, de Tocqueville said, and it is not good to be alone.

Many people run from the kind of isolation Samuelson endured out in the Lost Horse Valley, hoping to drown out their loneliness by the mere proximity of other bodies, in the brewery chatter of a hundred conversations.

But we all know that being close doesn’t mean we’re making contact.

We can be sitting on our couch, right next to our spouse, and still feel vast space separating us—the space created by old resentments; by misunderstandings, cross-purposes, and withdrawals; or simply by our inability to put into words what we think and feel.

What sort of space is that which separates a man from his fellows and makes him solitary? Thoreau asked. I have found that no exertion of the legs can bring two minds much nearer to one another.

Going online, where millions of people compete to be heard, can sometimes make the isolation worse. We move past one another so fast, we despair of ever having a meeting of minds.

And yet, sometimes I read a post, click the heart, comment, and suddenly, there’s that spark—real contact—and I am astonished.

The Void—the empty space that separates us from one another—paradoxically holds within it, I think, the secret that allows us to cross it.

In isolation we meet ourselves: our insecurities and fears, our dreams and disappointments, our confusions and muddled need. We have to face all the inner turmoil that keeps us from making real contact with others.

In a desert the sand blasts away at our painted surfaces, exposing the pure metal underneath, and it’s only there—metal to metal—where the electric current of true contact can flow.

“My God, My God,” Jesus cries on the Cross, “why hast thou forsaken me?”

What is the meaning of that cry if not that our redemptive communion comes only under the full weight of our total isolation?

When I was in my 20s, I tried to ride my bicycle across the country—all by myself. It was the loneliest I’ve ever felt.

To relieve the isolation, I slipped Shakespearean sonnets into the map case of my handlebar bag, and I memorized them as I pedaled.

One of my favorites was Sonnet #30, where Shakespeare describes one of those “sessions of sweet silent thought” that turns sour. We start thinking about the past: all the things we wanted but failed to get, all the time we’ve wasted, all the friends and lovers we’ve lost, all our grievances.

And yet, he writes, the mere thought of a dear friend makes all those woes disappear.

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past,

I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought,

And with old woes new wail my dear time’s waste;

Then can I drown an eye, unused to flow,

For precious friends hid in death’s dateless night,

And weep afresh love’s long since canceled woe,

And moan th’ expense of many a vanished sight.

Then can I grieve at grievances foregone,

And heavily from woe to woe tell o’er

The sad account of fore-bemoanèd moan,

Which I new pay as if not paid before.

But if the while I think on thee, dear friend,

All losses are restored and sorrows end.

I never made it across the country on that first bicycle trip. I hit a head wind in Kansas that blew straight out of Oz, and I gave up. I hitched a ride with two retirees in a Winnebago who drove me to a bus station where I bought a Greyhound ticket home.

A year later, I tried again, but this time, I brought a friend. We crossed the Void together, went clear through from Oregon to North Carolina.

I think Samuelson, the old crazy Swede, was right: the key to life is making contact any which way we can: with others in conversation, with nature in silence, with God in prayer.

But making contact begins in the contact we make with ourselves—in the Void that strips us down, naked and afraid, to our loneliness and need.

If you like the art, please click the heart. It increases my visibility on the Substack platform. Thanks!

The answers are always found in the damn paradoxes....

Beautiful as usual. ❤️❤️

What a ravishing meditation on loneliness, and the fierce, fragile ways we try to bridge it. Samuelson, that mad Swede with a hammer and a hunger, belongs in a lineage of accidental philosophers — those who don’t write books, but boulders, who don’t seek followers, but witnesses. His chiseled creed — Nature is God. Evolution is the Mother and Father of Mankind. The Key to Life is Contact.— reads like the distilled echo of a mind too raw to lie, too alone to pretend.

And how modern, indeed. Before Instagram captions and Substack essays, he was microblogging in stone, sending dispatches into the desert wind like digital flares before the digital existed. He wasn’t a nobody, he was the original poster. The OG influencer, minus the filters.

But here’s my take: contact is not the key to life. It’s the wound through which life leaks in. That ache for contact — relentless, maddening, sacred — is what animates us, what keeps poets scribbling, prophets howling, and a man talking to a volleyball. It’s not the connection that defines us, but the reaching for it. The longing is the thing. Ask Rilke. Ask Orpheus. Ask the desert wind.

You are right to invoke Shakespeare and Thoreau and that terrible, holy cry from the Cross. All of them naming, in their own lexicons, the fundamental human predicament: we are with and yet without. Proximity is not intimacy. Noise is not communion. We are loneliest in rooms full of people, scrolling through a thousand faces we will never touch.

But perhaps we should stop treating the Void like a failure. Maybe it’s a condition. A necessary haunting. The sand-blasted silence in which the truth of a self is revealed—not as an endpoint, but as a frequency we can finally hear. And from that frequency, real contact is possible. Not mass-produced. Not algorithmic. But slow. Singular. Like your sonnet in the handlebars. Like a post that inexplicably catches fire in a stranger’s soul.

So here’s to Samuelson. And to Wilson. And to Shakespeare and the Kansas wind. Here’s to the nobodies writing into the Void. Not because they’ll be heard, but because they must speak. Because that, too, is contact: the act of making a mark —even if the rock never replies.