There's A Stranger in Your House

What I Learned From Living With Portraits Of People I Don't Know

It was fourth of July weekend 2019 at the local carnival.

I had found a bench where I could sketch either the crowd standing on line at the Tilt-A-Whirl or the people trying for goldfish at the Ping Pong Toss.

I had been sketching for half an hour when an old man shuffled over to me and asked if he could share my bench.

“Of course,” I said. “But if you do, I might have to draw you.”

“Lucky you,” he said, chuckling.

I love sketching carnival scenes, but the old man quickly became the most interesting thing in my line of sight.

“I think I will sketch you, if you don’t mind,” I told him.

“Sitting still is all I do at my age,” he replied.

What a head! It looked like it has been chopped out of a block of wood. His underbite fascinated me; it made him look like a living cartoon. Combined with a smile that never seemed to leave him, his protruding jaw gave him an expression of bemused determination.

When I finished my sketch, I asked him to sign his name. You see what he wrote: Handsome Andrew Ramos, 1-26-28, Greek.

He was 91, he knew he was a sight, and he was proud of it.

When his children and his grandchildren returned from the rides, they oo’ed and ah’ed over my sketch, but not because it was good.

They liked the sketch because it captured Andrew’s likeness, and they loved him. They could tell that his good spirits and his kindly ways had won me over as well.

My artist friends tell me that portraits of strangers are difficult to sell; florals are the easiest, they say. When people buy portraits, they mostly go for pictures of themselves, their family, and their friends.

Given a choice between hanging Van Gogh’s portrait of his postmaster or a portrait of their dog, most people would choose their dog.

It’s understandable.

Home is a sanctuary from anonymity, a comfortable den of familiar faces. The global population is now 8.2 billion people. The world is full of strangers; we don’t need them hanging on our walls.

But this way of thinking overestimates both the strangeness of strangers and the familiarity of our family and friends.

I studied portraiture with a fabulous Chicago artist named DonYang, so I have a lot of portraits on my walls. It is astonishing how quickly the faces of these strangers have become familiar.

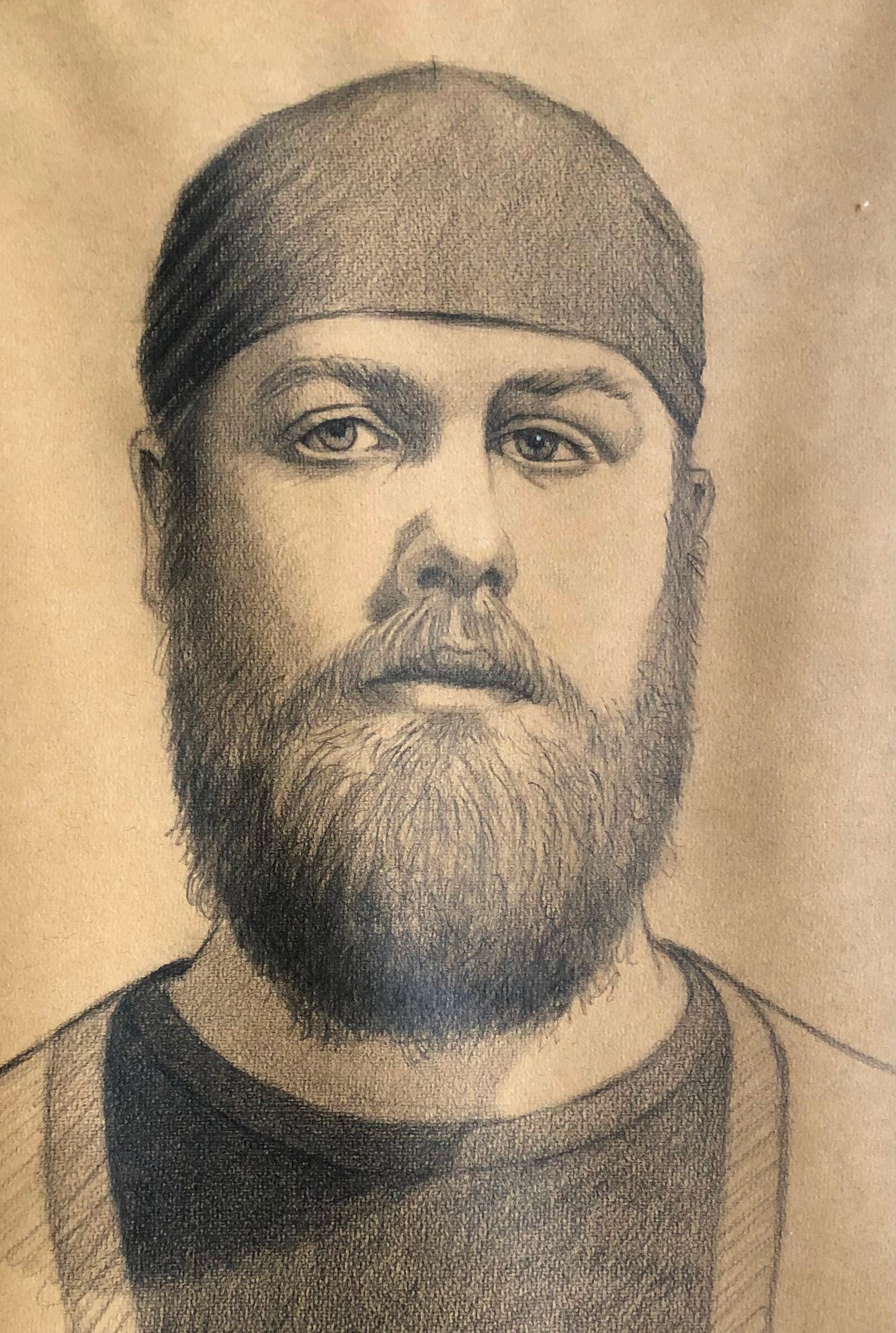

Take Jesse.

I don’t know Jesse. He was a model in class. After two live sessions, I never saw him again. But his portrait now hangs at my front door with a prominence usually reserved for the family patriarch.

Whenever I answer the doorbell, get my mail, or clear the living room floor for yoga, this big, sad-eyed young man in beard and bandana watches me.

Within a week of my hanging his portrait, Jesse was part of the family. The reason was simple.

I began seeing in Jesse’s face things which I saw or wanted to see in myself. Jesse looks like a gentle giant—a big man with a boy’s heart—and that’s how I like to see myself. He embodies an ideal: a combination of physical strength and emotional vulnerability. Virility with sensitivity.

To draw him, I had to objectify him—take the measure of his proportions—but when I look at his picture, I make him a part of me. I subjectify him.

If portraits of unknown men like Jesse prompt projections of my own ego ideals, portraits of unknown women provoke romantic fantasies.

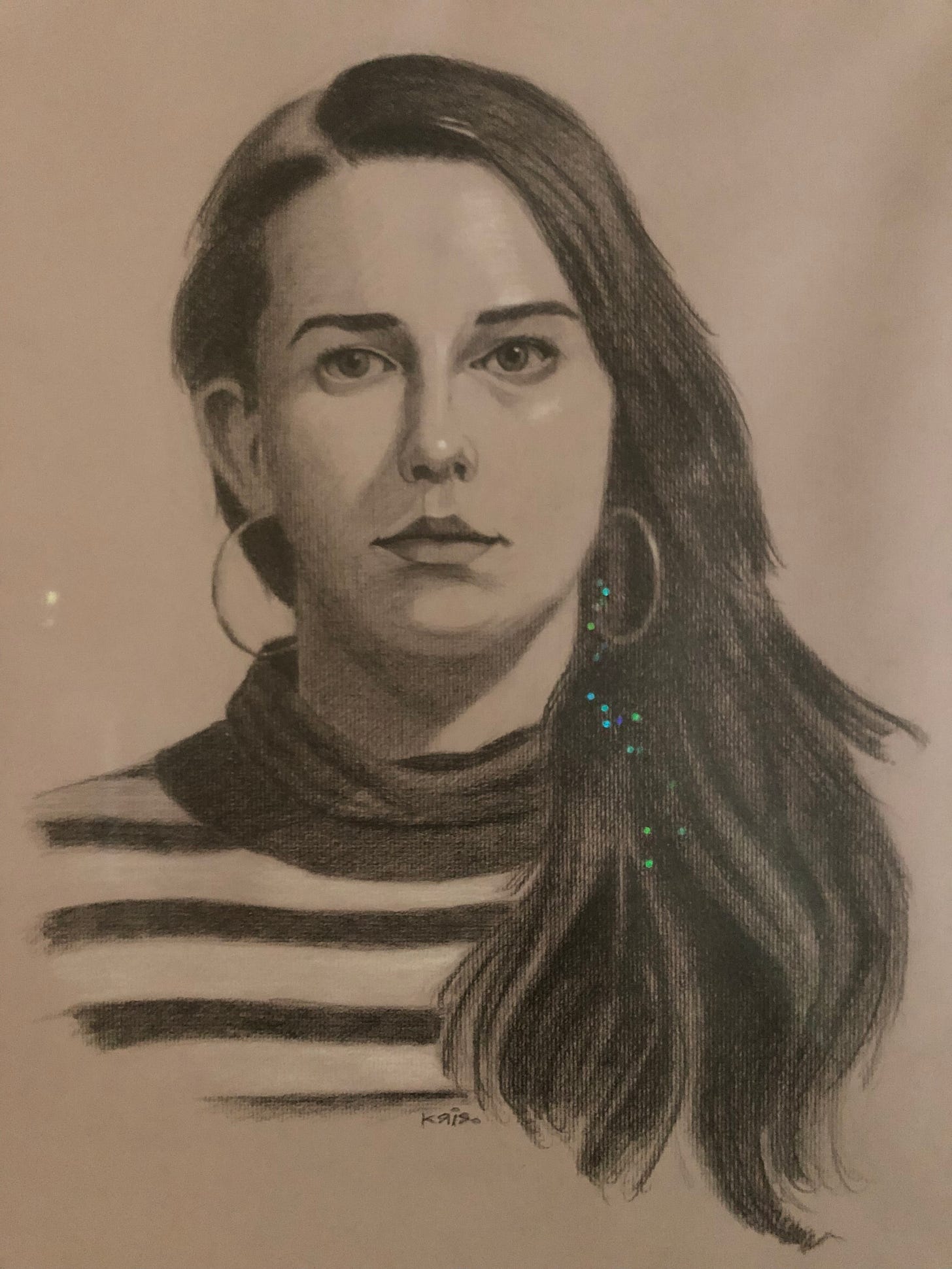

Take my Pirate Girl, another model I studied for two live drawing sessions.

I don’t remember her name. She was “Pirate Girl” before she had even settled into the model’s chair. It was, of course, the earrings, the striped shirt, and the swashbuckling sweep of her black hair.

I tried to see her as accurately as I could, of course, but underneath my attention to proportions and placement ran the fantasy of the female pirate: independent, wild, lawless, dangerous, exotic.

We see the opposite sex through our stories of adventure and romance, the dreams of love we get from books, movies, and TV. Men and women both do it. For every Elizabeth Swann there is a Jack Sparrow.

It is astonishing how often we see others through such crazily unrealistic lenses.

No matter how strange the face, we quickly make it familiar by projecting onto it something of ourselves—our ideals or our fantasies.

It’s good to remember because it is a key obstacle to love.

How many relationships begin when we meet a person who embodies a favorite fantasy? We are all of us casting-directors searching for people to play roles in our own movie. What a joy it is when we find another person dying to play the role opposite the one we ourselves most want to play!

But love is not the projection of mutually satisfying personal fantasies.

Love holds in check its own projections, not in a futile effort to be “objective,” but to open oneself up to the inner life of another. It does not constrain others by its own needs and expectations.

Love uses one’s own experiences to imagine how another is feeling and thinking. It goes a step further when it seeks out those sides of others we “just don’t get”—the stranger within us.

And then love takes one final step by reaching into the mystery of another’s being. It embraces the unknown, letting go of what we can’t control in another.

Love makes us vulnerable to the unpredictable surprise in us all.

“Love makes us vulnerable to the unpredictable surprise in us all.” - what an awesome awesome read this week - you got so many styles in your inkwell!!

Every time I read this, it goes a little deeper. ❤️