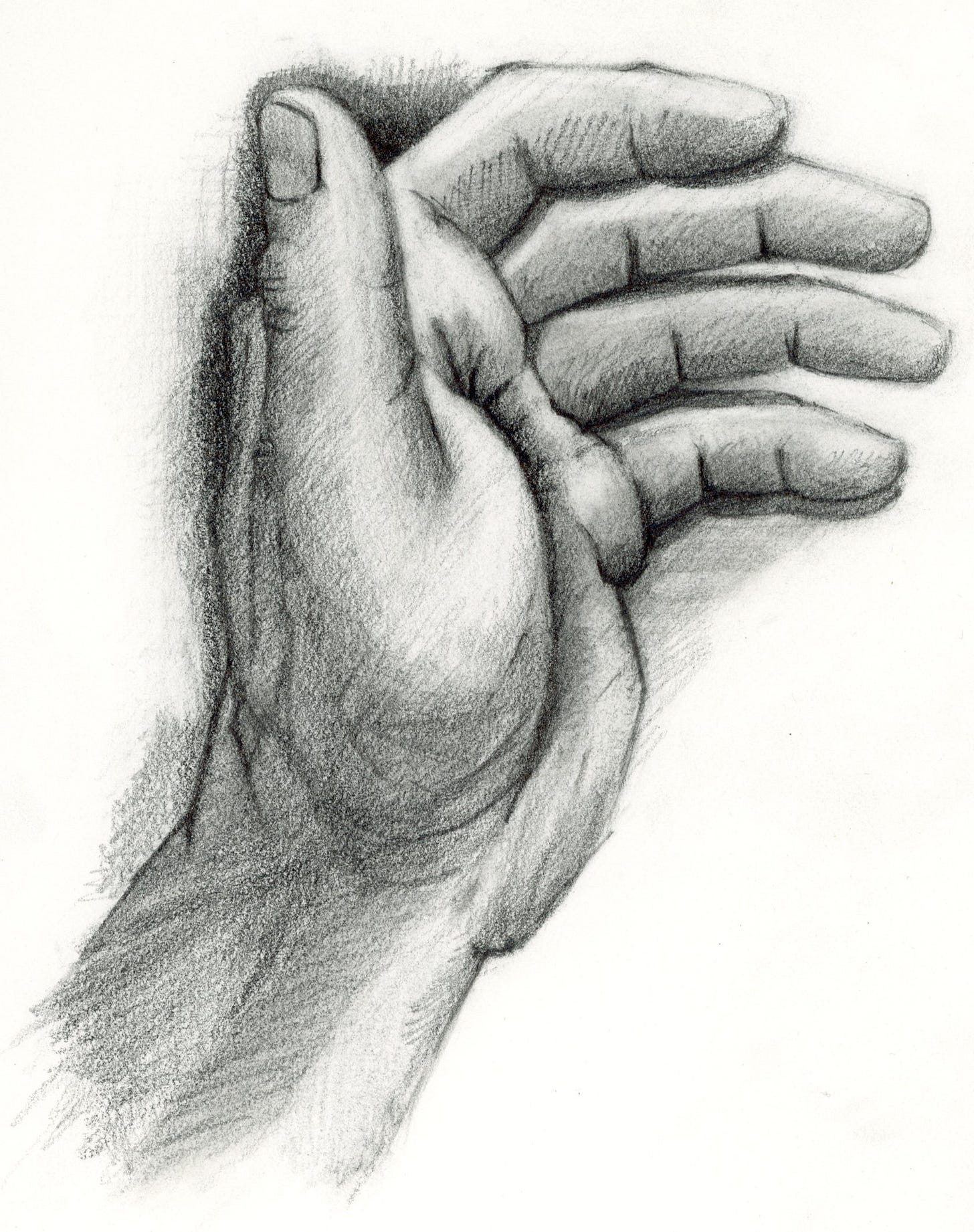

My left hand, shown in my drawing above, has suffered.

I was 10 when its trials began. My father believed America’s greatest educational establishment was football and signed me up to play in a Long Island youth league.

In our first scrimmage, I dove to make a tackle. The runner kicked me in the hand, broke the pinky and middle fingers, and popped the top half of the ring finger clean out of its socket to form a perfect right angle with the bottom half.

It was a revelation.

For the first time in my life, I realized I could break. Like a toy. I didn’t HAVE a skeleton; I WAS a skeleton!

It was the first of many indignities the poor hand would suffer. Cysts—little sacks of water—grew inside the bones, making them brittle and easily broken. Before I was 15, the surgeon had to go in twice to drain the cysts and pack the holes with bone scraped from my hip.

The last time I broke my hand, I was a junior at a Christian college in Nampa, Idaho. My orthopedic surgeon was no more than a veterinarian, a boozy hick trained on livestock.

I woke up with pins in my hand. He had hammered them into my metacarpals to keep the contraption from falling apart.

Two weeks later the cow doctor tried to take them out with what looked like barnyard pliers. He shot the hand with a local anesthetic and cut into it through the back, exposing the muscle and bone, but I couldn’t look.

I felt him, though, rooting around with the pliers, trying to grip the head of a pin, but he couldn’t quite get one. I don’t think the doc was used to working on small bones.

He grew sweaty, frustrated, and finally, furious, muttering countrified curses under his whiskey breath. Throwing caution to the wind, he turned the hand over, shot it with a little more juice, and cut a new hole, this time through the palm.

If the back door of the farmhouse is locked, you might as well try the front. From the palm side it was much easier to get a grip on the pin, but the damn thing was stuck like a nail in a board. It refused to budge.

That’s when I finally looked.

I was amazed. I was standing outside myself looking at the insides of my own body. If breaking my fingers the first time had been a revelation, this was a religious experience, except that instead of looking inside and finding that I had a soul and that Jesus loved me, I looked inside and saw machinery.

It was like discovering I was a robot.

One of the best things about being young is thinking you’re indestructible. Breaking my hand so often dispossessed me of that beautiful and empowering illusion a little earlier than I would have wished.

The vulnerability made me cautious and sealed my reputation as a crybaby. Every accident, no matter how small, was a Code Red, every mishap an occasion for flashing lights and sirens. I milked my miseries for all they were worth.

Today, my poor left hand is weak. The fingers bend over the palm like an old man over his cane. At rest, they go fetal, curling up in a pitiful collapse of habitual self protection. The pads of the palm surround the slash of its pain. The hand remembers.

Pleasure fades. Only trauma abides, but trauma is just life; the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” come with the territory. I drew my hand because it cried out to be drawn. The old pain needed a release more attractive than a whine.

Cartooning stretches the world; it allows me to exaggerate my emotions, but drawing from life demands I look into things like my hand more dispassionately. I look without all the hoopla of emotion, and low and behold, when I have finished, I find the emotions are there after all, but in a measure proportionate to the thing itself.

A sober eye, I’ve learned, can also be a saving grace.

Thanks Sally. I think I’d like to interview both those relatives and get their stories on paper!

"I was amazed. I was standing outside myself looking at the insides of my own body. If breaking my fingers the first time had been a revelation, this was a religious experience, except that instead of looking inside and finding that I had a soul and that Jesus loved me, I looked inside and saw machinery.

It was like discovering I was a robot."

Beautifully written. It sounds like you've made it to the other side of this trauma ❤️